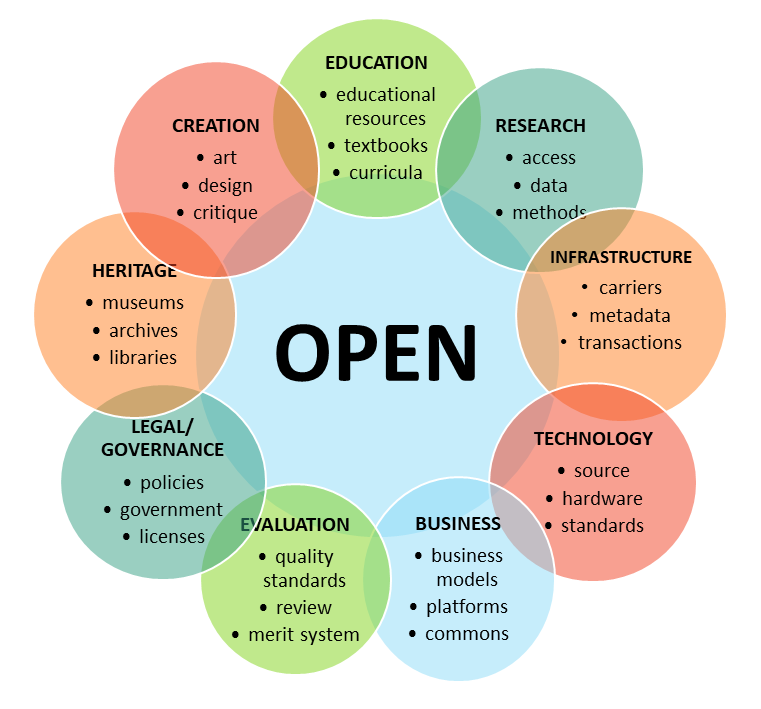

OpenAI has been around since 2015 but wasn’t a household name until late 2022 when ChatGPT made LLMs accessible to everyday consumers. The company was originally founded with a mission to ensure the eventual development of artificial general intelligence (AGI) that benefits all of humanity “unconstrained by a need to generate financial return.” The ‘open’ in OpenAI deliberately invokes positive connotations: open source software/hardware, open access publication, open data, open educational resources (OER) — all movements infused with a spirit of doing things for public benefit as much as or more than for private profit.

Yet as soon as OpenAI exploded in popularity going into 2023, there were already criticisms that they weren’t living up to the ‘open’ in their name. Models like GPT-4 were no longer open models: the company decided to disclose nothing about their training set used, the architecture of the model, the hardware used, the training method, and so on, partly in the name of safety (AI may eventually be a dangerous tool in the wrong hands) but more so because of the “competitive landscape” according to co-founder Ilya Sutskever.

OpenAI has also since sought to remove the umbrella non-profit control over its for-profit subsidiary elements (as of mid-2025, the toned-down restructuring plan may be a public-benefit corporation, still a far cry from the current non-profit setup).

All this has me thinking a lot lately about open movements and the commons.

AI built on the back of open data

It’s no secret that I’m a huge fanboy of Wikipedia and other projects from the non-profit Wikimedia; indeed, in 2024 I was awarded a Wiki Scholar fellowship to build connections between academia and the open knowledge movement. In projects like Wikipedia, countless individuals contribute their work and time to the commons, to the public benefit of all: indeed, any edits you make on Wikipedia are under the creative commons CC BY-SA 4.0 license meaning that others can use, share, and remix or build upon the work (even for commercial purposes) as long as the derivative work also remains free and open in the same way (i.e. under the same license).

This means some Wikipedia contributors get miffed when they see a self-published e-book sold for profit on Amazon that is just repackaging Wiki articles that countless volunteers put their blood, sweat, and tears into researching, composing, editing, and updating.

This common and understandable reaction is what Molly White calls “wait, no, not like that” moments:

“When a developer of an open source software project sees a multi-billion dollar tech company rely on their work without contributing anything back? Wait, no, not like that.

“When a nature photographer discovers their freely licensed wildlife photo was used in an NFT collection minted on an environmentally destructive blockchain? Wait, no, not like that.

“And perhaps most recently, when a person who publishes their work under a free license discovers that work has been used by tech mega-giants to train extractive, exploitative large language models? Wait, no, not like that.”

As White points out, a natural impulse by creators and commons contributors may be to pull away from openness, perhaps switching to non-commercial licenses or, worse, hiding work behind paywalls and stricter copyright. But every restriction added is also a removal of the spirit of openness, a step away from the free spirit that defines all of the open movements (‘free’ as in open to others’ access, freely accessible to the commons, as opposed to ‘free’ as in free beer).

You simply can’t avoid all “wait, no, not like that” situations without giving up the benefits of free and open access. Every step to wall off use by bad actors ends up also walling off the work from the commons in some way. A scientist may choose to avoid open access publication of their research so that LLMs don’t train on their writing, but that means putting their science behind a paywall that makes it only accessible to the wealthy or privileged (meanwhile, the publisher of that journal may decide to sell all the work to an AI company for training anyway). The more we try to stop “wait, no, not like that” situations — the more walls and barriers we erect — the less free and open our knowledge is, and the more the commons shrinks.

What White articulates so well in her article, though, is a different threat posed by AI companies training LLMs on open data and knowledge.

AI gobbling up the commons…and possibly itself

The real threat, she points out, comes when gigantic tech companies vampirically scraping content from sources like Wikipedia end up damaging or killing off those very projects they benefit from. For example, AI companies are currently creating massive amounts of automated traffic imposing huge bandwidth loads on infrastructure at Wikimedia and other sources in the commons. Meanwhile, despite some progress in LLMs adding citation links, overall AI systems send little traffic back to the original sources and thus reduce their visibility and viability. “[T]hey are destroying their own food supply”, White points out.

Meanwhile, as LLM use becomes ubiquitous we are facing an additional crisis where the internet is getting filled with AI-generated content that is mixed in with and often indistinguishable from genuine human content. More and more, we are inundated not just with obvious AI “slop“, but also reading AI-generated mundane content attributed to humans and interacting with AI-powered bots we think are people. For example, the debate subreddit r/ChangeMyView was recently part of an unethical experiment where LLMs successfully persuaded people who thought they were discussing controversial topics with fellow humans. Even published books are becoming filled with who-knows-how-much AI content.

The proliferation of AI content all over the web also means that the next generation of LLMs will be training not just on human language (like pre-LLM Wikipedia or the pirated books of libgen) but also on their own output. And AI researchers have warned that this kind of cannibalistic training on its own output can lead to training issues and even, in some cases, to model collapse. Similar to a .jpeg that gets copied and reposted over and over (losing pixels and becoming fuzzier every time until it’s unrecognizable) LLMs might fail when they start to train on their own output, a self-consumption dubbed AI autophagy (Alemohammad et al., 2023). As one paper states, “[w]e find that indiscriminate use of model-generated content in training causes irreversible defects in the resulting models” (Shumailov et al., 2024). Yes, synthetic data may be a valuable part of the training for future models, but not when such AI autophagy is completely uncontrolled (Xing et al., 2025).

Search and links replaced by AI overviews

Meanwhile, AI is threatening the open web as we know it in other ways. Google, by far the most popular search engine, inserts AI Overviews at the top of search results such that many queries might be answered by AI before a user ever scrolls further down to the actual web links. Meanwhile, Google’s AI Mode — a separate system that’s more of a wholesale replacement for traditional web search — also largely hides links to sources, instead encouraging users to continue in conversation with the LLM rather than clicking through to elsewhere. Sources are footnotes, rather than the prime destination they were in traditional search.

But of course Google is getting this very AI-generated information from those web sources, sources which have for decades now relied largely on search engine traffic to survive. Many publishers are panicking, as AI summaries and chatbots threaten the long-dominant business model of ad-supported web search.

And yes, in some cases the user experience may be better this way. As LLMs get more accurate and hallucinate less, who wouldn’t prefer a direct answer to their queries instead of combing through a pile of sponsored links and dubious sources based around search engine optimization (SEO) rather than accurate information? Google was already ruining its own search experience, as I discussed in a footnote on my recent enshittification post, so isn’t it better to skip search altogether and let an LLM do the browsing for you?

But there’s a larger problem here when search engines stop sending traffic to the websites that provide their knowledge base (or when users turn to chatbots for what they used to use web search for). Those sources may start to dry up; AI may be starving off one of its main sources of food. As some have put it, Google is burying the web alive [paywalled]1.

“Google’s push into productizing generative AI is substantially fear-driven, faith-based, and informed by the actions of competitors that are far less invested in and dependent on the vast collection of behaviors — websites full of content authentic and inauthentic, volunteer and commercial, social and antisocial, archival and up-to-date — that make up what’s left of the web and have far less to lose. […] [T]he signals from Google — despite its unconvincing suggestions to the contrary — are clear: It’ll do anything to win the AI race. If that means burying the web, then so be it.”

What we risk losing

Benj Edwards argues that as AI floods the web, we must protect human creativity as a natural resource, lest we risk “a gradual homogenization of our cultural landscape, where machine learning flattens the richness of human expression into a mediocre statistical average.” Tech companies are treating our creative works and culture “like an inexhaustible resource to be strip-mined, with little thought for the consequences.”

Just as strip-mining, clearcutting and overfishing threaten those natural resources, AI companies fighting for the upper-hand in what Sutskever called the competitive landscape threaten to undermine the resources behind their own technology and success.

Edwards briefly surveys some possible solutions for a more sustainable ecosystem of human creativity: legislation, licensing and royalty systems, opt-ins or opt-outs, preservation and patronage efforts, collectively-owned AI, and technical defenses to indiscriminate training. None feel compelling or convincing on their own, as it’s likely there’s no stopping many of the shifts that are coming, but I’m glad to see us exploring whatever options we can to minimize the damage and side effects of the sudden proliferation of AI into the web and everyday life.

Personally, I grew up on the open internet, back before most traffic consisted of people on five big social media sites reporting screenshots from one of the other four. Back before ads were the primary support for hosting and content2. Back when people posted on forums and usenet for community and shared interests. For a long time, great swaths of the internet didn’t feel so icky and enshittified precisely because they weren’t for-profit. People wrote websites and blogs and software out of curiosity and passion, for community and fulfillment, to discuss and debate and learn, to share, to connect.

That stuff’s still out there. People will always write, even when AI gets to the point it can write just as well. People will always create art. People will always seek to share and connect, not to make money, not as a side hustle, but because that’s what humans do. We create.

I wish there was a way to get back to an internet that isn’t based around advertisements, that isn’t focused on maximizing engagement and attention for the sake of ad revenue. One step in that direction would be regaining more control over the algorithms that currently shape our social media feeds (be it through more user-controllable, interoperable protocols like those behind Mastadon and Bluesky, or through something as simple and powerful as RSS). We don’t have to let multi-billion dollar tech companies dictate where our attention goes (and with it our time and our mood and our energy) as they shift our feeds away from friends and things you’ve selected to instead show you more ads and AI-suggested posts/reels/accounts.

Meanwhile, that’s also why I continue to host my own website and blog (brianwstone.com), freely accessible and ad-free in the original spirit of the open web, just as I’ve done for the past 25 years across all my other sites and blogs. Even though I know my hard work — and yes, I write without any AI — will be sucked up by AI companies and used to train their models, I still want to put my creative work out there in the free and open commons. Just like I continue to contribute to Wikipedia.

References

Alemohammad, S., Casco-Rodriguez, J., Luzi, L., Humayun, A. I., Babaei, H., LeJeune, D., Siahkoohi, A., & Baraniuk, R. G. (2023). Self-consuming generative models go MAD. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2307.01850

Shumailov, I., Shumaylov, Z., Zhao, Y., Papernot, N., Anderson, R., & Gal, Y. (2024). AI models collapse when trained on recursively generated data. Nature, 631, 755-759. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07566-y

Xing, X., Shi, F., Huang, J., Wu, Y., Nan, Y., Shang, S., Fang, Y., Roberts, M., Schonlieb, C., Del Ser, J., & Yang, G. (2025). On the caveats of AI autophagy. Nature Machine Intelligence, 7, 172-180. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-025-00984-1

Footnotes

- For those unfamiliar, archive.is is one of many ways to get around publisher paywalls. I have complicated feelings on whether this is a good thing or bad. I think the ad-supported, ad-centered model has been one of the worst things to happen to the internet — and perhaps our culture in general — and it’s a big part of why our web experience get shitter and shittier over time. Paywalls, subscriptions, microtransactions — these things are promising alternatives to an ad-supported information ecosystem, and I wholeheartedly want to support the good work of journalists, news organizations, and other publishers which certainly can’t do their work for free. But also, paywalls have made the WWW a dysfunctional experience compared to the original hyperlinked web that Tim Berner’s Lee brought us. As Scott Alexander pointed out years ago, paywalled articles don’t just incentivize clickbait headlines, they also become part of the public discourse — often with major political, social, and medical ramifications — without being accessible to all. During the COVID-19 pandemic, important information with health, safety, and economic implications was published behind newspaper paywalls. At any rate, I’m of mixed feelings but lean toward providing openness while still encouraging those who can afford it to subscribe to and support the publications that provide valuable content. ↩︎

- Cory Doctorow’s recent podcast for the CBC (“Understood: Who Broke the Internet) discussed the early internet in their first episode Don’t Be Evil. Talking about how unusual it was for ads to show up on the internet: “There was this minor explosion when a couple of lawyers decided to mass post onto a bunch of usenet groups an advertisement for their law firm. And this was so scandalous to everyone back then that there was just, you know, weeks and months, really years of debate, about whether or not this should be tolerated; should these people be kicked off these newsgroups? Should we have rules that say, like, we don’t want people selling things on the internet?” ↩︎

Leave a Reply