A key component of scientific practice has long been reproducibility: the expectation that any experiment performed should yield the same basic results when someone else performs it; in other words, the expectation that other people can follow your procedure and reproduce your findings. Even the most famous and respected scientists should have their work checked.

Ideally, when scientists share their findings in the latest peer-reviewed journal article, they include all of the methodological steps that went into their research so that another scientist could repeat their steps (i.e. perform a replication of the study) and — hopefully — find the same outcome. If the replication succeeds, we become more confident in the original results, and if it fails, we become much more skeptical of them.

Actually carrying out the steps and performing these replication experiments is crucial because, in practice, many research findings published in peer-reviewed scientific journals turn out — later on — to not replicate when tried a second or third time. A drug that initially appears to successfully treat a medical condition turns out, when tested again, to not actually work, or to not work as well.

Back in 2005, John Ioannidis rang the alarm bell for medical research when he argued most published findings in that field were likely false (Ioannidis, 2005). Part of the problem comes from the mistaken assumption that a single research study showing an effect should be taken as convincing evidence that the effect is real; in reality, even the best-designed studies carry some chance of a false positive result (e.g., the statistics say a treatment works when in reality it doesn’t). Instead of relying on a single study to guide our understanding of how the world works, we should look at the bulk of the evidence combined across many studies (i.e., many replications), and only if those studies generally agree should we be confident in the effect. Yet we live in a world where shiny, new findings get press while the slow, boring work of reproducible science just isn’t sexy, and so we continue to fall into the trap of paying too much attention to single studies and too little to the weight of replicated evidence.

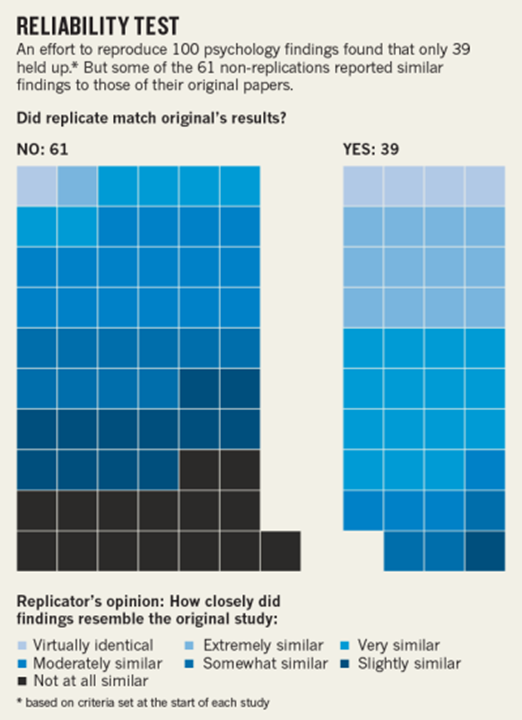

Medicine isn’t the only field that has struggled with this curse. In the field of psychological science, when many well-publicized results turned out to not replicate (for example, being exposed to words related to old age doesn’t actually make people walk slower), it led to a reckoning for the field — what some have called a “replication crisis”. Since then, psychology researchers have come together in large collaborations to estimate the scale of the problem and to determine which research findings reproduce. For example, in 2015 a large group of scientists collaborated together to try replicating 100 studies that had been published in three respected psychology journals. Many of the original results didn’t hold up, and those that did tended to show much weaker effects than initial research had suggested (Open Science Collaboration, 2015).

Others have found similar results, with effect sizes decreasing when original research is repeated by other scientists (e.g., Klein et al., 2018). There are many reasons why this might be the case, but a couple cultural practices in scientific research and communication contribute heavily to this: (1) a tendency to use research designs that have too little statistical power (e.g., too small of a sample size), and (2) a bias by journal editors and even scientists themselves toward publishing or trying to publish positive results while not publishing results that don’t find an effect (so-called null results).

While it might initially seem depressing that so many research findings don’t replicate, or end up much weaker than initial findings suggested, it is actually quite encouraging to see how much attention the issue has gotten, how many changes have been made to the cultural practices of day-to-day science (the way it’s actually carried out in practice, in contrast to the idealized version of the scientific method taught in introductory science classrooms). Researchers obviously do care about these issues — a lot — and are working hard to fix them, to shore up the foundations on which our scientific fields are built, and to bring back an emphasis on the value of reproducibility for science.

However, all of this work trying to replicate past results may be for naught if researchers don’t take the newer evidence from replication studies into account. Science is supposed to be a self-correcting process where we update our beliefs objectively based on the evidence that comes in, but scientists are humans, and as humans, are susceptible to the cognitive biases that plague all of us. That includes, for example, confirmation bias (the tendency to selectively notice, prefer, or remember evidence that fits our preexisting beliefs), belief perseverance (when beliefs persist even after the evidence is contradicted or removed), and general motivated reasoning (the tendency to bias how we reason through information in a way that suits our preexisting goals or preferences).

So the question is: when scientists are confronted with new, updated information about previously-published results will they update their beliefs to match the new evidence, or will they persevere in their old beliefs?

A study from late 2021 addressed that very question (McDiarmid et al., 2021). Before carrying out large-scale replications of some psychological findings, these researchers took a survey of more than 1000 other scientists working in the field and asked them about their belief in those findings. For a sub-group (half of those being polled), the researchers also told them in detail about the plans to carry out replication studies and asked them to predict how they would adjust their beliefs depending on different ways the replication studies might turn out. (The other half of those being polled were not told about the replication plans at this stage so that they could serve as a control condition to ensure that merely being asked ahead of time wouldn’t change their opinion of the replication results later).

Then the replications were carried out and all the surveyed scientists were shown the replication results and asked once more about their (updated) belief in the relevant psychological effects.

What did the study find? Sure enough, the scientists tended to update their beliefs in the direction of the new evidence, and roughly as much as they predicted ahead of time that they would update their beliefs (given that particular replication result). Which is great! As a minor caveat, though, the scientists did tend to adjust their beliefs less than might be expected based on the weight of the total evidence, suggesting a mild bias toward sticking with their original beliefs, a sort of belief inertia.

Overall the study found that psychological researchers demonstrated less motivated reasoning than one might expect. For example, those surveyed did not change their opinion about the quality of the replication study design once they learned of the results, even if doing so would have helped preserve their original beliefs. They didn’t dig in their heels or try to explain away the results after the fact in a biased way that would maintain their old beliefs; indeed, they showed the very quality of self-correction that is essential to successful science.

Of course, all of the above describes the surveyed scientists as a group, but were there any individual differences among the scientists? On the one hand, they found that the scientists with the most intellectual humility updated their beliefs a bit more than those with less intellectual humility (not surprising, really). On the other hand, one might expect that scientists most familiar with cognitive biases (like confirmation bias and belief preservation) would be more likely to update their beliefs with new evidence, but that didn’t seem to be the case here.

If these latter results replicate (see what I did there?) and generalize to non-scientists, it brings up questions about whether, say, educating the public about cognitive biases would actually provide the hoped-for protection against motivated reasoning and also whether traits like intellectual humility can be taught or trained — subjects for a future post.

Meanwhile, one last thought about the study: just because the surveyed scientists reported an updated level of belief in the direction of the new evidence doesn’t mean their beliefs actually changed in that direction or that much. After all, it’s possible they were over-estimating in their report to the researchers (perhaps to look or feel more like they think scientists should act, or to act how they thought the researchers expected them to act, etc.).

There is another angle to studying how much scientists change their beliefs to incorporate the results of replication attempts, and that’s by investigating the behavior of how scientists later cite those studies. For example, if an earlier result is overturned (so to speak) by high-quality replication work that strongly contradicts the original study, will that change how future journal articles by other scientists in that specialty then end up citing such work?

Another study in late 2021 investigated this for a handful of large-scale, high-quality replication attempts of four well-cited psychology findings where the original findings were strongly contradicted and outweighed by the new data (Hardwicke et al. 2021). Previous work had appeared to show such things as a “flag priming effect” (seeing an American flag once makes you support Republicans more even months later) or the “facial feedback effect” (where forcing your muscles into a smile shape or frown shape changes your emotion), whereas the high-powered replications of those earlier results drastically undermined the original claims.

If scientists are self-correcting their beliefs in light of new evidence, you would expect cases like this to lead to fewer citations of the original work or more unfavorable mentions (at the very least, fewer favorable citations). On the other hand, we might find belief perpetuation, where scientists continue citing the original research uncritically without taking the contradictory work into account or providing any counterarguments to it.

So, what happened in this particular case study of the four effects that were strongly contradicted by high-quality, large-scale replications? In the years following the replications, there was a small decrease in favorable citations of the original (now contradicted) work and a small increase in unfavorable citations. So thankfully some scientists did take the new information into account; however, the self-correction here was modest and underwhelming, and in the end, the large majority of citations to those old articles remained favorable citations. Even if someone found the replication work unconvincing despite it being pre-registered, multi-laboratory research with large sample sizes, they should at least mention the replication and perhaps argue against it, but that’s not what was found: generally work citing the original article didn’t mention the replication, and when it did, a counterargument was only offered about half the time.

So psychological scientists as a whole appear to demonstrate some significant belief perseverance and/or a serious lack of awareness about replication work, and self-correction appears to be harder or slower than it should be.

This isn’t unique to psychology, of course. In the biomedical literature, retracted articles continue to be cited afterward in large numbers, almost always as if it were still valid (Budd et al., 1998). In epidemiology, observational studies that are later contradicted by much more powerful randomized clinical trials still end up cited favorably at a high rate (Tatsioni et al., 2007). This is probably less an issue with any one field of science and more due to the fact that scientists are human and thus susceptible to the same cognitive biases as all of us, like confirmation bias, belief perseverance, the continued influence effect, and motivated reasoning. It may be that self-correction in science takes a longer time scale than what’s been looked at in these kinds of citation-based studies (e.g., Hardwicke et al. 2021 were looking at citations 3-5 years after the contradictory replication was published), but any attempt to speed up the process of self-correction will probably need to take into account the cognitive biases of the people involved.

References

Budd, J. M., Sievert, M., & Schultz, T. R. (1998). Phenomena of retraction: Reasons for retraction and citations to the publications. Journal of the American Medical Association, 280(3), 296-297. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.280.3.296 [PDF]

Hardwicke et al. (2021). Citation patterns following a strongly contradictory replication result: Four case studies from psychology. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 4(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/25152459211040837 [PDF]

Ioannidis, J. P. A. (2005). Why most published research findings are false. PLoS Medicine, 2(8), e124. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0020124 [PDF]

Klein, et al. (2018). Many labs 2: Investigating variation in replicability across sample and setting. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 1(4), 443-490. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515245918810225 [PDF; PsyArXiv preprint: PDF]

McDiarmid et al. (2021). Psychologists update their beliefs about effect sizes after replication studies. Nature Human Behavior, 5, 1663-1673. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01220-7 [PsyArXiV preprint: PDF]

Open Science Collaboration (2015). Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science, 349(6251), aac4716. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aac4716 [PDF]

Tatsioni, A., Bonitsis, N. G., Ioannidis, J. P. A. (2007). Persistence of contradicted claims in the literature. Journal of the American Medical Association, 298(21), 2517-2526. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.298.21.2517 [Sci-Hub PDF]

Leave a Reply