Have you ever been discussing something with a person who disagreed with you and they just didn’t seem to listen? Maybe they twisted your words and interpreted what you said in the worst of ways? Indeed, maybe you yourself have been arguing with some ignorant anonymous jerk in the comments section of social media and found yourself framing their argument in a way that sounds absurd in order to win the rhetorical battle, so to speak.

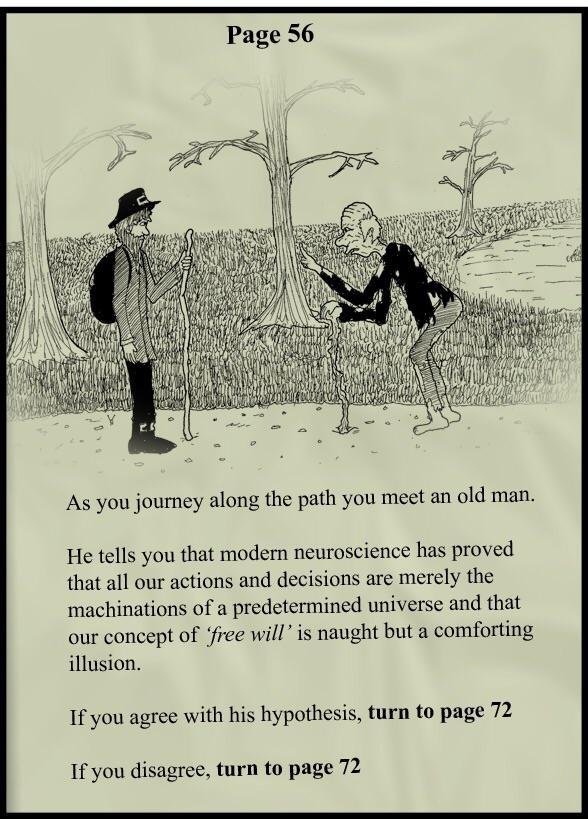

Or perhaps you’ve witnessed a debate about free will that went like this:

Determinist: “Choice is an illusion. All of our actions were determined by a complex chain of causes and effects going back to the beginning of time.”

Free Will Defender: “So you’re we have no choice, that we’re not responsible for our actions — you’re saying we should let murderers off the hook and not lock them up since they had no choice but to do what they did! That’s madness!”

Now, in the moment, this might seem like a winning rhetorical jab from the free will defender: surely no one wants to leave murderers just running around doing as they wish, so the determinist position is hogwash! But if we’re being intellectually honest, the determinist isn’t necessarily saying that at all. We’ve jumped to a conclusion (that the determinist is fine with murderers running around) that is rather uncharitable of their actual view.

Instead, the determinist might (more charitably) be interpreted as saying that murderers did what they did because of a long chain of influences — all past experiences, their entire history of rewards and punishments, and all other environmental+genetic influences we can think of — and couldn’t have done anything else, but also that the police officers and lawyers and prison guards involved in the justice system are similarly determined to act as they do (to chase the murderer and lock him up), just as most of us are determined by our past experiences and cultural+genetic programming to find the murderer repulsive, and so on. Indeed, just as the free will defender and the determinist are themselves both caused to hold their current beliefs and to have this very discussion.

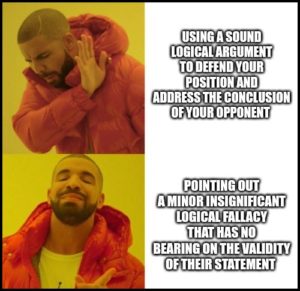

Rather than trying to “gotcha” the other side in any debate, you might do well to first try to interpret their statements and arguments in the best way possible. If, having considered their position in this way, you still find the best interpretation of their argument wanting and you can poke holes in this stronger version, then do so, but don’t attack the weakest and least charitable interpretation of what the other person is saying.

This is a principle in philosophy and rhetoric known as the principle of charity. Sometimes the principle is phrased as: try to understand ideas before criticizing them.

It doesn’t mean that we must accept bad arguments or that we shouldn’t challenge ideas which are repulsive (the principle of charity is not meant as an unbreakable law). Instead, just recognize that a lot of the time when people make an argument for or against something, they take conversational shortcuts or leave out certain implicit premises. You’ll be more likely to get at the truth — and also to have a productive conversation — if you give others the benefit of the doubt rather than attacking the weakest and worst way of interpreting their words.

The Ethics Centre has a nice example:

Let’s take same sex marriage. Someone might say they support it because “all kinds of love should be treated the same”. Taken literally, this is obviously false. We shouldn’t treat the love a stalker shows to their victim the same way we treat the love a close romantic couple share. They’ve taken a shortcut that affects how their argument could be interpreted.

Using the principle of charity, we would interpret their argument as “all kinds of love between consenting adults should be treated the same”. For a discussion to be successful, we need to do our best to understand what a person means rather than what they explicitly say.

And honestly, we use the principle of charity at a much smaller level in our conversations every day. When someone sweating in a hot room says “this place is an oven!” we don’t assume they are claiming to be in an actual device for cooking food; we gracefully — and indeed, automatically — interpret their statement as figurative. This is more charitable (and productive) than taking their statement literally.

Yet when we’re in a heated debate with someone on the opposite side of a topic we feel strongly about granting a charitable interpretation is no longer automatic and requires some effort. Someone pro-choice might hear their opponent state that “life begins at conception and it’s wrong to take a life” and the pro-choice person might be tempted to counter “but I know you’re actually okay with ending life — we kill living organisms all the time, like killing living plants to eat and killing living microbes when we wash our hands.”

The pro-choice person may be on to something here and is introducing a fact that’s certainly relevant to our explorations of ethics around killing things that are alive. Likely, the person who supports forced birth is indeed fine with killing living microbes by washing their hands. However, the pro-choice person here is seizing on a somewhat weak interpretation of their opponent’s statement: the person who supports forced birth could be interpreted as making a stronger argument. For example, perhaps what they really mean is:

(Premise 1) A zygote involves living human cells, not currently conscious, feeling, or thinking, but with a new and unique set of DNA which is involved in a process of growing into what will — in the right circumstances — become a conscious, feeling, thinking person (a cooing baby, a babbling toddler, eventually an adult).

(Premise 2) Not only do persons deserve protection, but so do potential persons. After all, we think it’s right to protect a sleeping person from death even if they’re not currently conscious, feeling, or thinking, because we know that in normal circumstances they will wake up and the conscious, feeling, thinking person will exist again.

(Conclusion) Therefore, even though the zygote is “just a clump of cells”, it’s the type of living thing that deserves protection in a way that microbes and plants don’t.

This may or may not be a convincing argument to you (I can certainly think of some counters), but it is likely a stronger argument than taking the initial statement of the forced birth advocate literally as “it’s wrong to kill any living thing at all”. Yes, it means filling in implicit premises they didn’t explicitly state, but you’re less likely to get stuck in an unproductive argument nit-picking about something they didn’t really intend to say or knocking down the weakest straw-man version of their position.

Sometimes you might be giving your opponent too much credit. Perhaps they did indeed mean the weaker version, the weaker interpretation of their argument. In that case, it might be helpful to address that argument directly rather than addressing a stronger argument they didn’t mean to make at all; you may be more likely to change their mind, or even just clarify their own position and help build a more nuanced understanding. Even if “we kill living things all the time” doesn’t directly address the stronger argument for forced birth, it may be helpful for getting the forced birth advocate to think about what they mean by life in this context and may make them think more precisely about their own principles (which may not be as well-defined as they previously assumed).

So, again, it’s not a hard-and-fast rule that following the principle of charity is the best way to discuss or debate. Yet regardless of whether it’s the best way to change someone’s mind in a given circumstance, it is still a great tool for helping you find the truth. Because if you can only defeat the weakest arguments against your own position, it’s hard to feel confident in that position; whereas if you can directly address the strongest counters to your position and still find your position convincing, you stand on firmer epistemic ground.

And you might find that applying the principle of charity doesn’t just help you bolster your existing views (beware confirmation bias!) or convince others to be less wrong, but it also provides you with a habit of mind to help you think more clearly and avoid leaping to as many erroneous conclusions in the future.

On a related note:

Itamar Shatz at Effectiviology has a nice write-up about the principle of charity (with more examples).

Leave a Reply